In July 2010 Rob and I flew off on a great adventure, following Brendan! But we travelled the northern arc route in the secure comfort of modern aircraft from Newcastle upon Tyne; via Amsterdam to Portland Oregon.

St. Brendan (Brendan the Navigator or Brendan the Voyager) was born in Ireland in 484. He was a Celtic monk who travelled far and wide in the 6th century, possibly even following the same northern arc route to North America from Ireland. In 512 Brendan was ordained to the priesthood; between the years 512 and 530 he built monastic cells at Ardfert, at Shanakeel or Baalynevinoorach, in County Kerry and at the foot of ‘Brandon’ Hill. It was from here that he set out on his most famous voyage.

The accounts of his voyages were well known in past times, but many are inclined to think it was all myth and make-believe.

But his voyage from Ireland to the North Americas has been reconstructed by British navigation scholar, Tim Severin, in 1976. He had meticulously worked to make sure that the leather skinned boat he had made was, for all intents and purposes, identical to the ‘mythological’ boat, described in the 11th century book, ‘Navigatio’, in which St. Brendan and the Irish monks crossed the North Atlantic centuries before the Vikings. He proved it could be done.

Severin sailed this boat from Ireland to Newfoundland via Iceland and Greenland, demonstrating the accuracy of its directions and descriptions of the places Brendan mentioned in his epic, and proving that a small boat could have sailed from Ireland to North America.

His book “The Brendan Voyage” is fascinating.

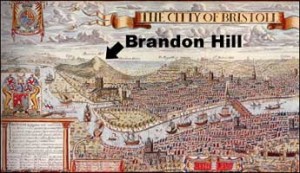

Many places still carry the name of Brendan, or Brandon

(another form of the same name)

Rob and I had both lived in and around Bristol, in South West England, for many years till we moved to the North East. It was a very important seaport, the estuary of the River Avon, especially for those heading for the “new World” across the Atlantic Ocean. As John Cabot left on his New World voyages of discovery, in 1497 he would pass Brandon Hill, named after St. Brendan. Before the Reformation, there was a shrine on top and the sailors would actually pray to St. Brendan for protection instead of praying to the God that St. Brendan served. That is why the shrine was removed after the Reformation, though the hill still bears the same name.

Back to Brendan: On the Irish Kerry coast, he built a curragh, or large coracle, of wattle, covered it with hides tanned in oak bark softened with butter, set up a mast and a sail, and after a prayer upon the shore he and his company of monks set off into the unknown, guided by their faith in God.

This is the prayer that is believed to have been said by Brendan on that shore

Saint Brendan’s Prayer:

Shall I abandon, O King of mysteries, the soft comforts of home?

Shall I turn my back on my native land, and turn my face towards the sea?

Shall I put myself wholly at your mercy, without silver, without a horse, without fame, without honour?

Shall I throw myself wholly upon You, without sword and shield, without food and drink, without a bed to lie on?

Shall I say farewell to my beautiful land, placing myself under Your yoke?

Shall I pour out my heart to You, confessing my manifold sins and begging forgiveness, tears streaming down my cheeks?

Shall I leave the prints of my knees on the sandy beach, a record of my final prayer in my native land?

Shall I then suffer every kind of wound that the sea can inflict?

Shall I take my tiny boat across the wide sparkling ocean?

O King of the Glorious Heaven, shall I go of my own choice upon the sea?

O Christ, will You help me on the wild waves?

For seven years they voyaged to find the Promised Land of the saints, and amazing stories are told of his wanderings in the ‘Navigatio’ and other documents. Eventually they reached the “Terra Repromissionis”, the Paradise or Promised Land, a most beautiful island with luxuriant vegetation.

Maybe the Irish can claim they discovered America?

This claim rests in part on the account of the Vikings who found a region south of the Chesapeake Bay, which is a large estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. It was called “Irland ed mikla”(Greater Ireland),

and on stone carvings discovered in West Virginia dated between 500 and 1000 A.D. Analyses by experts indicate that these carvings are written in Old Irish using the Ogham alphabet. According to them, “the West Virginia Ogham texts are the oldest Ogham inscriptions anywhere in the world. They exhibit the grammar and vocabulary of Old Irish in a manner previously unknown in such early rock-cut inscriptions in any Celtic language….. Early Christian symbols such as Chi-Rho monograms (Name of Christ) and the Dextra Dei (Right Hand of God) appear at the sites together with the Ogham texts.”

The Irish monks were renowned as sea-farers centuries before Columbus. Tradition says that they reached Iceland and explored even farther afield in the Atlantic. Some scholars who long doubted that the voyage described by Brendan could have made it to North America have reconsidered their position based on the research and pilgrimage of Tim Severin.

After many years of seafaring Brendan at last returned to Ireland. Brendan also founded a monastery at Inis-da-druim (now Coney Island, County Clare), about the year 550. He journeyed to Wales, and later to the Scottish Island of Iona, and was a disciple of St. Finian. After three years in Britain he returned to Ireland and did much good work in various parts of the land. The great mountain that juts out into the Atlantic in County Kerry is called Mount Brandon, because he built a little chapel atop it, and the bay at the foot of the mountain is Brandon Bay. He founded many churches and other Christian communities but his most famous, founded in 557, is Clonfert in Galway. This huge monastery housed 3,000 monks, whose rule of life was very austere, and also included a convent for women initially placed under the charge of his sister, St. Briga.

Brendan died at Enach Duin, now called Annaghdown, in 577, on a visit to his sister while she was abbess of a convent there. Despite a life of exceeding piety and many dangerous travels, he had great anxiety about the last journey of death. His dying words to Briga are reported to have been: “I fear that I shall journey alone, that the way will be dark; I fear the unknown land, the presence of my King and the sentence of my judge.”

Brendan’s feast day is celebrated on May 16.

It is well established that Columbus went to look for St. Brendan’s Isle when he discovered the West Indies. As a student of the University of Pavia, Columbus would have learned of Brendan’s voyage from the manuscripts brought there, seven hundred years previously, by Dugal, student and founder of the University of Pavia.

On the eve of his great voyage aboard the Santa Maria in 1492 he wrote: “I am convinced that the terrestrial paradise is in the Island of Saint Brendan, which none can reach save by the Will of God.